“I love it. It is wild with adventure.”

Henry Starr describing the bandit life in the Old West before he was shot to death in a gunfight in Arkansas.

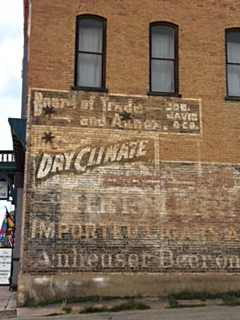

Leadville. You can find it yonder nearly 11,000 feet above sea level, known in the late 1800s and early 1900s as the best route for Easterners to head West. And while you experienced the most surreal scenery surrounding it all, you were lucky if you traversed there to survive the elements—both human and natural.

Leadville. You can find it yonder nearly 11,000 feet above sea level, known in the late 1800s and early 1900s as the best route for Easterners to head West. And while you experienced the most surreal scenery surrounding it all, you were lucky if you traversed there to survive the elements—both human and natural.

I offer this little preamble because Pete and I just visited this strange Colorado town caught in the web of the past and present woven by ghosts of gun shooters and prostitutes and gamblers and sheriffs and pioneer families and miners and millionaires and jilted lovers and some of the most famous and infamous characters in America’s history—including, John “Doc” Holiday, Carrie Nation, Baby Doe Tabor, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and even Oscar Wilde!

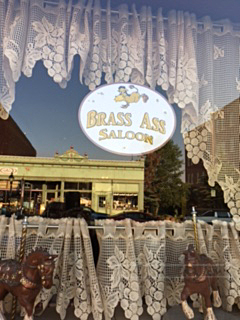

Their bodies might have long exited this god-forsaken city but, trust me, their phantasms are very much alive. In the midst of today’s Leadville coffee shops and hotels and restaurants and antique shops and pubs and theatres and historic sites with packs of tourists everywhere, those Wild West spirits ain’t dead yet.

Pete and I thought for sure we were about to have nothing but great luck on this two-day escape. First thing starting out that morning, Pete had won $8 (my lucky number) in a gas-station lottery ticket. Whoo-friggin-hooo!!!! But it didn’t take long before we began to feel a disconcerting sense.

Pete and I thought for sure we were about to have nothing but great luck on this two-day escape. First thing starting out that morning, Pete had won $8 (my lucky number) in a gas-station lottery ticket. Whoo-friggin-hooo!!!! But it didn’t take long before we began to feel a disconcerting sense.

You know how you have a gut feeling about something and if you’re wise you listen to it? Well, I had one of those, holy-shit-let’s-not-go-there moments even as we drove our mountainous climb in time to experience yet another Colorado site we’ve never seen. Foreboding stuff made its debut. Two hideous truck-loads of precious pigs on their way to slaughter—glimpses of their sweet pinkness could be seen as they crowded together on their way to impending deaths. A graceful deer lay dead on the side of the road and right across from it one of her family was mortally wounded and then shot by a group of the highway patrol—a puff of smoke from the gun report could be seen as we sped on. All in counter-balance to the breathtaking beauty putting on a nature show the likes of which we had never seen before. Buffalo roaming a verdant meadow. Lush vegetation—infinite acres of pine and aspen, wildflowers, crystal lakes and roaring creeks. Life’s yin and yang spread before us.

And then we arrived in Leadville.

The perfect timing of our intro to this mountain world was that it followed our splendid visit the day before to the Denver Museum of Art and an entire Cowboy-Native American retrospective from Remington to Curtis sculptures, photographs and paintings to legions of other deeply moving works of art showing the drama of life back then—featured in the fabric of Americana. Including some of our most cherished movies of all time, many directed by the King of Westerns himself, the great John Ford. So with that taste of the sensory Wild West images fresh on our culture palettes of course we figured that visiting Leadville was a natural segue.

The perfect timing of our intro to this mountain world was that it followed our splendid visit the day before to the Denver Museum of Art and an entire Cowboy-Native American retrospective from Remington to Curtis sculptures, photographs and paintings to legions of other deeply moving works of art showing the drama of life back then—featured in the fabric of Americana. Including some of our most cherished movies of all time, many directed by the King of Westerns himself, the great John Ford. So with that taste of the sensory Wild West images fresh on our culture palettes of course we figured that visiting Leadville was a natural segue.

However we didn’t anticipate the heaviness that we began to feel there. Because though it’s alive with history in every twist and turn (in the Sixties it apparently was a hippy haven), there is a pervasive sadness, a feeling of a ghost town on the edge trying with all its might to stay relevant and contemporary and youthful.

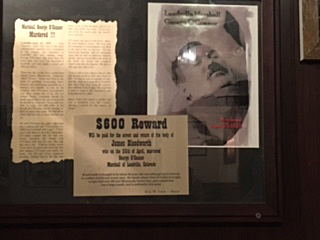

But still it was impossible to ignore the fact that life during those olden days were though abundantly successful, filled with culture and opera and theatre and saloons and gobs of strike-it-richers noted for their extraordinary wealth, it was also an achingly raw and wrenching time. Infant mortality was rampant. Death was around every corner in a place that knew horrifically icy, mountainous snowbound challenges and disease and lawlessness that was boundless in its lack of rules of any kind. Public hangings and shootouts and a legendary story of a beautiful lady who ended her years as a mad woman impoverished and waylaid from her once privileged world of wealth caught in a love triangle of infamy. We walked through her tiny cabin where she had been found frozen to death. I could feel her screams of anguish in every molecule within that crypt-like world where she lived and died alone for over thirty years.

But still it was impossible to ignore the fact that life during those olden days were though abundantly successful, filled with culture and opera and theatre and saloons and gobs of strike-it-richers noted for their extraordinary wealth, it was also an achingly raw and wrenching time. Infant mortality was rampant. Death was around every corner in a place that knew horrifically icy, mountainous snowbound challenges and disease and lawlessness that was boundless in its lack of rules of any kind. Public hangings and shootouts and a legendary story of a beautiful lady who ended her years as a mad woman impoverished and waylaid from her once privileged world of wealth caught in a love triangle of infamy. We walked through her tiny cabin where she had been found frozen to death. I could feel her screams of anguish in every molecule within that crypt-like world where she lived and died alone for over thirty years.

And so Pete and I spoke to some of the seasoned natives. Delightful, intelligent, caring elders who did all they could to keep the Leadville stories alive. They were wonderful people and eager to share what they knew; so refreshing within that pall of sadness. I mean so many antique stores were filled with sheriff’s badges and photographs and books and postcards written by long-lost lovers and siblings and parents, their formal language and lovely cursive an art form long gone.

A popular restaurant had their walls peppered with museum quality hats and boas from the 1800’s as well as photographs of dead sheriffs and bad guy hangings attended by huge crowds. It was a challenge enjoying a hearty breakfast with the photos of the dead within inches of our coffee.

A popular restaurant had their walls peppered with museum quality hats and boas from the 1800’s as well as photographs of dead sheriffs and bad guy hangings attended by huge crowds. It was a challenge enjoying a hearty breakfast with the photos of the dead within inches of our coffee.

What occurred to us looking beneath all the curios and signs and vintage paraphernalia abounding is that cruelty and violence and sorrow is unfortunately the story of the human condition—all ages and stages of life. We have always loved and always killed each other. And I have to wonder when will this madness ever end? When humanity ends and we start over with a clean slate?

The feeling we had of Leadville was the relief of leaving it. Especially since poor Pete was simultaneously suffering from a raging gastrointestinal attack that definitely motivated us to get the hell out of Dodge way faster than we had planned. He said that it was a case of “Lead(ville) poisoning.” I know he was right because he was fine soon after we returned home. Before a bird dive-bombed into our car as we headed back down the mountain.

In 1883, Sitting Bull was a guest of honor at the opening ceremonies for the Northern Pacific Railroad. When it was his turn to speak, he said in the Lakota language, “I hate all white people. You are thieves and liars. You have taken away our land and made us outcasts.” A quick-thinking interpreter told the crowd the chief was happy to be there and that he looked forward to peace and prosperity with the white people. Sitting Bull received a standing ovation.

Oscar Wilde’s West

Thursday, 5th July, 2007

First published The Guardian by Sam Jordison

I’m writing this in Leadville, Colorado and frankly, I’m a little bit scared. I don’t regret coming here (so far). I love it. The place is enjoyably, though worryingly, “authentic”. I’ve already been unwillingly involved in a saloon discussion about whether a local I’ve never met and whose name I can’t remember is “a mummy’s boy”, I’ve have had to dodge my way home past fireworks flying up the street, and have noted with alarm that the average bicep size here is thicker than my waist.

I’m writing this in Leadville, Colorado and frankly, I’m a little bit scared. I don’t regret coming here (so far). I love it. The place is enjoyably, though worryingly, “authentic”. I’ve already been unwillingly involved in a saloon discussion about whether a local I’ve never met and whose name I can’t remember is “a mummy’s boy”, I’ve have had to dodge my way home past fireworks flying up the street, and have noted with alarm that the average bicep size here is thicker than my waist.

But bracing as life here is now, I can only imagine the storm that must have greeted the unwary visitor back in the 19th-century boom days when it was, by all accounts, the place that put the wild into west.

Back in 1883, Leadville was a frantically bustling town of 30,000 people – 29,000 of whom had arrived in the last six years, following the discovery of thick veins of silver in the area. At 10,200ft above sea level and overflowing with desperate fortune hunting miners and their hangers-on, Leadville could lay claim to being the highest and toughest town in the US. Hooch sellers made more money than mine owners, justice was a question of who could pull a gun fastest and the majority of local culture was to be found as bacterial growth on the food supplies that had to be shipped in by wagon train over the perilous mountain passes.

Curiously, however, this new town also had a rather splendid opera house, and it was to this ornate structure that the singularly incongruous figure of Oscar Wilde made his way during his 1882 lecture tour of the US, glittering with diamonds and done up (if contemporary accounts are to be believed) in a purple Hungarian smoking jacket, knee breeches and black silk stockings. And on what subject did Wilde choose to lecture the hard-bitten, hard-living miners?

Curiously, however, this new town also had a rather splendid opera house, and it was to this ornate structure that the singularly incongruous figure of Oscar Wilde made his way during his 1882 lecture tour of the US, glittering with diamonds and done up (if contemporary accounts are to be believed) in a purple Hungarian smoking jacket, knee breeches and black silk stockings. And on what subject did Wilde choose to lecture the hard-bitten, hard-living miners?

Surprisingly, this sensible-sounding talk does not appear to have gone down well. Even Wilde gave mixed reports, once claiming that: “I read them passages from the autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini and they seemed much delighted. I was reproved by my hearers for not having brought him with me. I explained that he had been dead for some little time which elicited the enquiry ‘Who shot him?'”

On a later occasion, however, he sadly admitted that his audience “slept as though no crime had ever stained the ravines of their mountain home.” Meanwhile, other accounts describe how the local stagehands decided that the great Irish playwright was a bit too “sissified” for their liking and pushed him off the stage into the orchestra pit.

Apparently, those same stagehands then marched Wilde off to Leadville’s notorious red light district, where they intended to humiliate him further by getting him dead drunk. Wonderfully, however, the aesthete triumphed. He drank his would-be persecutors under the table and proceeded to become so popular in the town that they decided to name a silver vein after him.

Apparently, those same stagehands then marched Wilde off to Leadville’s notorious red light district, where they intended to humiliate him further by getting him dead drunk. Wonderfully, however, the aesthete triumphed. He drank his would-be persecutors under the table and proceeded to become so popular in the town that they decided to name a silver vein after him.

This christening necessitated a ceremony in which Wilde was lowered to the bottom of a mine in a bucket (“I of course true to my principle being graceful even in a bucket”), ate an underground meal and smoked a cigar. “Then,” he explains, “I had to open a new vein, or lode, which with a silver drill I brilliantly performed, amidst unanimous applause. The silver drill was presented to me and the lode named ‘The Oscar’. I had hoped that in their simple grand way they would have offered me shares in ‘The Oscar’, but in their artless untutored fashion they did not. Only the silver drill remains as a memory of my night at Leadville.”

After the vein was named, Wilde and his new friends retired to yet another saloon where he saw what he described as “the only rational method of art criticism I have ever come across.” Over the piano there hung a notice: “Please do not shoot the pianist. He is doing his best…”

After the vein was named, Wilde and his new friends retired to yet another saloon where he saw what he described as “the only rational method of art criticism I have ever come across.” Over the piano there hung a notice: “Please do not shoot the pianist. He is doing his best…”

Predictably, Oscar had something clever to say on the subject. “I was struck with this recognition of the fact that bad art merits the penalty of death, and I felt that in this remote city, where the aesthetic applications of the revolver were clearly established in the case of music, my apostolic task would be much simplified, as indeed it was.”

At which point, I find it far too tempting to resist asking if anyone else can think of a good punishment for bad art – and to whom would you give it? With reasons.